Separation logic and bi-abduction

Separation logic

Separation logic is a novel kind of mathematical logic which facilitates reasoning about mutations to computer memory. It enables scalability by breaking reasoning into chunks corresponding to local operations on memory, and then composing the reasoning chunks together.

Separation logic is based on a logical connective

called the separating conjunction and pronounced "and separately". Separation

logic formulae are interpreted over program allocated heaps. The logical formula

holds of a piece of program heap (a heaplet) when it

can be divided into two sub-heaplets described by

and

. For example, the formula

can be read " points to

and

separately

points to

". This

formula describes precisely two allocated memory cells. The first cell is

allocated at the address denoted by the pointer

and the

content of this cell is the value of

. The second cell is

allocated at the address denoted by the pointer

and the

content of this second cell is the value of

. Crucially,

we know that there are precisely two cells because

stipulates that they are separated and therefore the cells are allocated in two

different parts of memory. In other words,

says that

and

do not hold the same value

(i.e., these pointers are not aliased). The heaplet partitioning defined by the

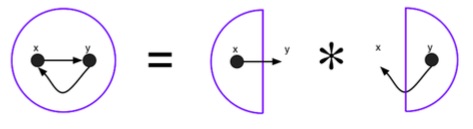

formula above can be visualized like so:

The important thing about the separating conjunction is the way that it fits

together with mutation to computer memory; reasoning about program commands

tends to work by updating -conjuncts in-place, mimicking

the operational in-place update of RAM.

Separation logic uses Hoare triples of the form

where

is the precondition,

a

program part, and

the postcondition. Triples are

abstract specifications of the behavior of the program. For example, we could

take

as a specification for a method which closes a resource given to it as a parameter.

Now, suppose we have two resources and

, described by

and we close the

first of them. We think operationally in terms of updating the memory in place,

leaving

alone, as described by this triple:

What we have here is the that specification (spec) described how

works by mentioning only one piece of

state, what is sometimes called a small specification, and in (use) we use that

specification to update a larger precondition in place.

This is an instance of a general pattern. There is a rule that lets you go from smaller to bigger specifications

Our passage from (spec) to (use) is obtained by taking

to be

to be

, and

to be

This rule is called the frame rule of separation logic. It is named after the

frame problem, a classic problem in artificial intelligence. Generally, the

describes state that remains unchanged; the

terminology comes from the analogy of a background scene in an animation as

unchanging while the objects and characters within the scene change.

The frame rule is the key to the principle of local reasoning in separation logic: reasoning and specifications should concentrate on the resources that a program accesses (the footprint), without mentioning what doesn't change.

Bi-abduction

Bi-abduction is a form of logical inference for separation logic which automates the key ideas about local reasoning.

Usually, logic works with validity or entailment statements like

which says that implies

. Infer

uses an extension of this inference question in an internal theorem prover while

it runs over program statements. Infer's question

is called bi-abduction. The problem here is for the theorem prover to discover a pair of frame and antiframe formulae that make the entailment statement valid.

Global analyses of large programs are normally computationally intractable. However, bi-abduction breaks apart a large analysis of a large program into small independent analyses of its procedures. This gives Infer the ability to scale independently of the size of the analyzed code. Moreover, by breaking the analysis into small independent parts, when the full program is analyzed again because of a code change the analysis results of the unchanged part of the code can be reused, and only the code change needs to be re-analyzed. This process is called incremental analysis and it is very powerful when integrating a static analysis tool like Infer in a development environment.

In order to be able to decompose a global analysis into small independent

analyses, let's first consider how a function call is analyzed in separation

logic. Assume we have the following spec for a function

:

and by analyzing the caller function, we compute that before the call of , the formula

holds. Then to utilize the specification of

the

following implication must hold:

Given that, bi-abduction is used at procedure call sites for two reasons: to discover missing state that is needed for the above implication to hold and allow the analysis to proceed (the antiframe) as well as state that the procedure leaves unchanged (the frame).

To see how this works suppose we have some bare code

but no overall specification; we are going to describe how to discover a

pre/post spec for it. Considering the first statement and the (spec) above, the

human might say: if only we had in the

precondition then we could proceed. Technically, we ask a bi-abduction question:

and we can fill this in easily by picking

and

, where

means the empty state. The

is recording that at the start

we presume nothing. So we obtain the trivially true implication:

which, by applying logical rules, can be re-written equivalently to:

Notice that this satisfies the (Function Call) requirement to correctly make

the call. So let's add that information in the , and while

we are at it, record the information in the

of the first

statement that comes from

.

Now, let's move to the second statement. Its precondition

in the partial symbolic execution trace

just given does not have the information needed by

, so we can fill that in and continue by

putting

in the

. While

we are at it, we can thread this assertion back to the beginning.

This information on what to thread backwards can be obtained as the antiframe part of the bi-abduction question:

where the solution picks

.

Note that the antiframe is precisely the information missing from the

precondition in order for

to proceed. On

the other hand, the frame

is the portion

of state not changed by

; we can thread

that through to the overall postconditon (as justified by the frame rule),

giving us:

Thus, we have obtained a and

for this

code by symbolically executing it, using bi-abduction to discover preconditions

(abduction of antiframes) as well as untouched portions of memory (frames) as

we go along.

In general, bi-abduction provides a way to infer a pre/post specs from bare code, as long as we know specs for the primitives at the base level of the code. The human does not need to write preconditions and postconditions for all the procedures, which is the key to having a high level of automation. This is the basis for how Infer works, why it can scale, and how it can analyze code changes incrementally.

Context: The logical terminology we have been using here comes from AI and philosophy of science. Abductive inference was introduced by the philosopher Charles Peirce, and described as the mechanism underpinning hypothesis formation (or, guessing what might be true about the world), the most creative part of the scientific process. Abduction and the frame problem have both attracted significant attention in AI. Infer uses an automated form of abduction to generate preconditions describing the memory that a program touches (the antiframe part above), and frame inference to discover what isn't touched. Infer then uses deductive reasoning to calculate a formula describing the effect of a program, starting from the preconditions. In a sense, Infer approaches automated reasoning about programs by mimicking what a human might do when trying to understand a program: it abduces what the program needs, and deduces conclusions of that. It is when the reasoning goes wrong that Infer reports a potential bug.

This description is by necessity simplified compared to what Infer actually does. More technical information can be found in the following papers. The descriptions in the papers are precise, but still simplified; there are many engineering decisions not recorded there. Finally, beyond the papers, you can read the source code if you wish!

Technical papers

The following papers contain some of the technical background on Infer and information on how it is used inside Facebook.

- Local Reasoning about Programs that Alter Data Structures. An early separation logic paper which advanced ideas about local reasoning and the frame rule.

- Smallfoot: Modular Automatic Assertion Checking with Separation Logic. First separation logic verification tool, introduced frame inference

- A Local Shape Analysis Based on Separation Logic. Separation logic meets abstract interpretation; calculating loop invariants via a fixed-point computation.

- Compositional Shape Analysis by Means of Bi-Abduction. The bi-abduction paper.

- Moving Fast with Software Verification. A paper about the way we use Infer at Facebook.